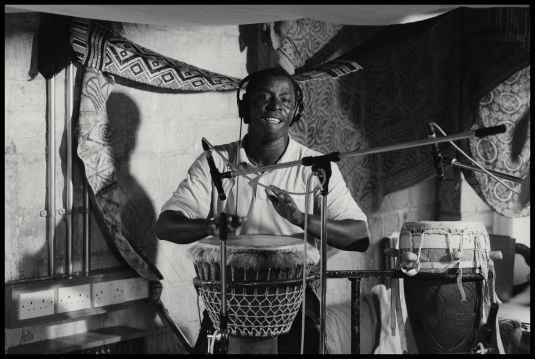

“One week in the middle of summer this craziness exploded in our Real World Studios. We had this week of invited guests, people from all around the world, fed by music and a 24 hour café. It was a giant playpen, a bring your own studio party. There’d be a studio set up on the lawn, in the garage, in someone’s bedroom as well as the seven rooms we had available. We were curators of sorts of all this living mass. We had poets and songwriters there, people would come in and scribble things down, they’d hook up in the café. It was like a dating agency, then they’d disappear into the darkness and make noises – and we’d be there to record it.” Peter Gabriel

Almost eighteen years in the making, Big Blue Ball grew from three extraordinary Recording Weeks at Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios in the summers of 1991, 1992 and 1995. They came as a practical response to a problem that became a great creative idea. The Recording Weeks were arranged to clear a space between block bookings from the likes of New Order so that Real World artists with the budget for just a day or two recording could come together en masse to deliver their own albums and work on some side projects, too. The atmosphere and spirit of it was very important. The location of the studios, the café space that was open day and night. Each room had a different atmosphere for getting down all manner of collaborations and experiments.

For recording engineer Richard Chappell, who was there on the ground getting it all on tape, “it used the facilities in the best possible way. It was what Real World was designed for. The way that it’s built, the way the rooms are put together, the spaces like the big room that really came into their own. I don’t think could have happened anywhere else.”

Hossam Ramzy, who had been invited to the Recording Week by Peter while touring Page and Plant’s No Quarter remembers it being “like Christmas, Eid, Byram and my Birthday thrown together in one. To co write with Peter, Natacha and my musicians was like another gear shift upwards. I found myself with my musicians experiencing something new. Something that opened their eyes to a style of collaboration they had never experienced before.”

Among the united nations of performers who found their way to Real World during those weeks were Billy Cobham, Papa Wemba, Hossam Ramzy and The Egyptian String Ensemble, Sinead O’Connor, Natacha Atlas, flamenco guitarist Juan Canizares, American singer Joseph Arthur, Afro Celts James McNally and Iarla Ó Lionáird, Japanese percussionist Joji Hirota, Jah Wobble, gospel group The Holmes Brothers, Justin Adams, Francis Bebey, Tim Finn, Marta Sebestyen, guitarist Vernon Reid, Chinese flute player Guo Yue.

And those are just some of the ones who made the final cut. But the party also included Nigel Kennedy, Remmy Ongala, Dan Lanois, Van Morrison (singing Sam Cooke’s That’s Where It’s At with The Holmes Brothers), and the amazing Terem Quartet of balalaika players (reportedly once members of the same tank crew). And then there was Joe Strummer’s impromptu entrance-hall encampment decked it out with drapes and candles and a four-track tape machine.

Iggy Pop dropped by, followed by celebrity couple of the day, Johnny Depp and Kate Moss. Even John Cage was there, in spirit at least; when news of his death came through during the first recording week, Penguin Café Orchestra leader Simon Jeffes, who was working in the ‘arcane’ studio in the same corrugated building that housed the 24-hour café, led his musicians through chord changes that spelled out the composers name C-A-G-E.

The project’s originators and curators were Real World founder Peter Gabriel and Karl Wallinger of World Party and The Waterboys. As Peter recalls, “The Big Blue Ball was a working name for a project that would pull in elements from all around the world. The title came from listening to an astronaut describe his experience of looking back at the earth. All other divisions seemed ridiculous and arbitrary, because there’s the planet, the whole thing – and that idea seemed to make a lot of sense for this project.”

It was also the title of a song Karl Wallinger had put in the pot early on. This, along with the likes of Everything Comes from You, featuring Sinead O’Connor, and Gabriel’s Burn You Up, Burn You Down, were first put down in 1991 and worked on in subsequent Recording Weeks.

“It was an amazing feeling, with all of it happening at once,” remembers Karl. “There were different producers in different studios. John Leckie, Phil Ramone, people you respect, it was fun to dive in – I’d do guest guitar in one room, a bit of singing in another.”

For Wallinger, the role of curator was “simultaneously doing opposite things –you want to give the sessions control and direction while trying to do the opposite, to create an anarchic space where people can add their piece with as little affectation as possible. That’s a fine line to tread, between too much authority and letting people go. It’s like being a mini local government – making sure there’s roads and bridges.”

Richard Chappell, who engineered and recorded the original sessions, remembers most of the collective projects happening upstairs in Peter’s room, with individual album projects getting done in the big studio. “Peter was at the centre of operations, but it wasn’t Peter’s project, it was a communal project in a writing, musician’s community.”

“It’s like a wall of sound coming at you, listening to the planet from outer space,” says Karl Wallinger of the final mix. “It’s a real world-view of music, a snapshot of the music-making continents at that time. It was easy to put an Egyptian string section with a Japanese drummer in the same room and have some sort of groove for them to follow, basically to invent a piece of music that people from all over the world could play on together.”

Holding the disparate elements in place is the backbone of the big drum tracks underpinning many of the songs. “Each one began with an eight-minute rhythm track,” remembers Karl. “That’s what was set up, that was the basic backbone. Everyone was in orbit around this groove, and there is a universal language of dance, of dance grooves. That groove is the one bit that’s non-denominational on the album.”

The other non-denominational bit is the time it’s taken - eighteen years from first groove to final mix – to get it finished. What the heck too them so long?

Even back in 1995, Karl Wallinger could see troubles ahead, “I don’t know how we’re going to finish things. It’s all very well recording but you see all these tapes building up and you think, it would be nice to get a finished track at some point.”

Still supervising the final mixes in January 2008, Richard Chappell concurs. “By the final recording week in 1995, there were people turning up to record everywhere – there were people in the toilet with a tape deck putting something down.” And they were running out of storage room for the tapes.

After the last Recording Week in 1995, the musicians and producers dispersed, the tapes stayed up on the shelves, and the Big Blue Ball all but sank from view until producer Stephen Hague (Pet Shop Boys, Robbie Williams, Mel C) came on board to begin cutting and comping the mess of recorded material Karl and Peter had put in the can. Tchad Blake (Peter Gabriel, Tom Waits, American Music Club) was tasked with the final mixing in 2007.

Not only was there the sheer volume of raw material to contend with, by the time they started on post production there was a major format change to overcome. “We set up this massive transfer system from tape to digital,” recalls Amanda Jones of Real World Records. “And Stephen Hague would sit there in the stone room, chopping and cutting with his computer, taking a line here and putting it there to bring this thing down to a listenable length.”

“I felt a bit like a prospector,” remembers Stephen Hague, “sifting through finer and finer screens, trying to highlight the best elements of each track and all the individual performances.” He takes the opening track Habibe as an example. “Habibe started life as an 18 minute jam by Natacha Atlas and an amazing improvised string section over a drone and percussion track. But I had a hard time coaxing it into any kind of shape until I introduced some chords to help support her melodies. I asked Peter if I was straying too far from the original recording, but he liked what he was hearing and was very supportive, telling me he just wanted the best setting for the main performances, and to make a great record, wherever that led.”

The recording week sessions were all about vibe and momentum and the buzz of having all that talent in one place for only a short time. “Work on one song often led to the start of a new collaboration, and a brand new track became that evening’s focus,” says Stephen. “There ended up being a lot of loose ends. I had a great fun helping to pull it all together...”

“It’s amazing its managed to come out,” says Karl. “There’s such a lot of stuff, a lot of things to iron out, I have a lot of admiration for the people who sat there and put it together. On some tracks it’s like there’s a football field of musicians coming at you.”

Making sense of these epic week-long sessions must have been extremely daunting. And very little of it came with a clear road map - Peter Gabriel reckons about 80 per cent of the material was generated on the spur of the moment. “There were 16 or 17 songs altogether. Different people would be leaders at different points while we were trying to steer all this craziness in the writing room above the big studio.”

And what of Big Blue Ball’s impact today, 13 years after the final sessions? “It’s a more apt time to release it now than ever before,” says Karl. “I think it’s actually gathered weight with time, because it’s people from all over the world playing together, just getting on together. There’s an iconic aspect about that which is probably more important now. Things have become more partisan. It’s a timely reminder of how you can cooperate.”

And it exudes an enormous joy de vivre of musical discovery, of finding common musical tongues that the Big Blue Ball has carried from the original spirit of the original sessions through all those years in limbo to the finished copy you have now. “After all these years, it’s a fine wine ready to be drunk,” says Peter Gabriel, “It was the most fun music making I’ve ever had. I’d love to do it again.”